Synthetic chemicals saturate modern food systems. They hide in pesticides, packaging, soil, water, and air. Their health and ecological costs are rising fast.

A recent Systemiq-Grantham Foundation report links chemical exposure to chronic diseases, fertility loss, and ecosystem damage. Conservative estimates put annual global damage at $1.4 trillion to $2.2 trillion, about 2–3% of global GDP.

The number of registered industrial chemicals reached about 350,000 in 2025. Yet only a small share underwent systematic hazard assessment. As a result, regulators often act after damage occurs. This approach increases both risk and long-term costs.

Experts argue for a hierarchy of solutions.

- Elimination ranks first.

- System redesign follows.

- Safer substitution comes next.

- Remediation remains essential but costly.

The shift also affects clean energy. Chemical manufacturing and cleanup consume large amounts of energy. At the same time, toxic pollution strains power grids, water networks, and waste systems. By contrast, cleaner chemistry can reduce lifecycle emissions and lower overall resource demand.

Europe has reduced hazardous phthalate use by about 90% within a decade through firm timelines. Precision agriculture and biological controls are reducing pesticide toxicity in major economies.

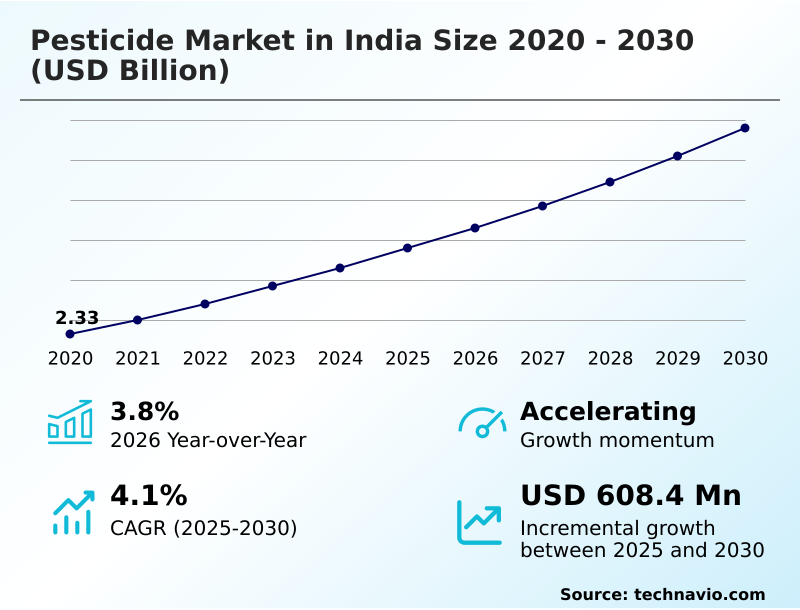

India faces similar risks. The country is among the world’s largest pesticide consumers and plastic users. Food packaging waste is rising. Chemical manufacturing also drives industrial electricity demand. Safe-by-design chemicals could lower energy use and pollution in India’s food and packaging sectors.

Persistent chemicals like PFAS pose another challenge. Experts estimate 42% of PFAS volumes could be phased out by 2030. Alternatives could replace about 95% by 2040.

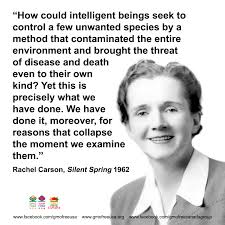

More than 50 years after Rachel Carson warned about synthetic chemicals, human exposure continues to rise at a rapid pace. However, governments, businesses, and investors now have the tools and the economic case to shift from cleaning up damage to preventing it through better design.

Therefore, the question is no longer whether action is possible, but how long society can afford to delay.

Reference- Reuters, EARTHDAY.ORG, National Geographic, The Guardian, Scientific American,

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.